For decades, construction scheduling in the United States has largely favored analytical methods like the Critical Path Method (CPM). However, a historically effective alternative – location-based scheduling – is making a comeback, driven by a need for more visual, practical project management. This approach, which prioritizes space as a critical resource, isn’t new; it has roots stretching back to the early 20th century, yet its adoption has been uneven.

Historical Precedents

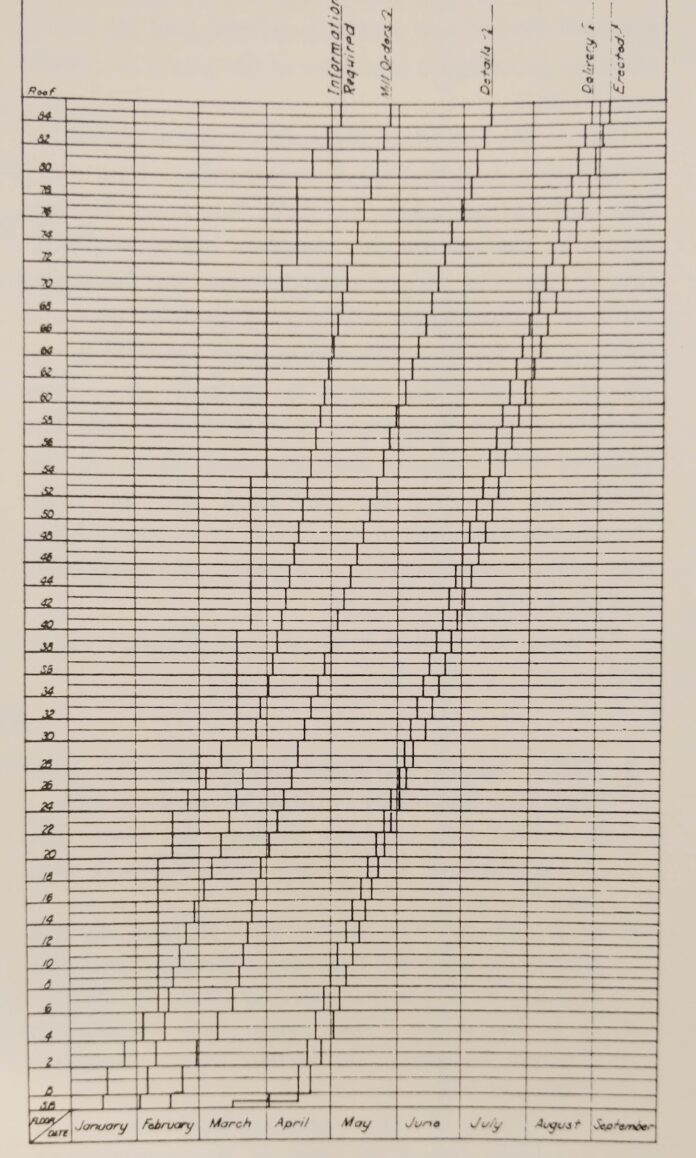

The concept of scheduling work based on location isn’t a modern invention. In fact, some of the earliest and most successful implementations occurred in the 1930s, most notably during the construction of the Empire State Building. Using a system closely resembling what is now known as a Line of Balance schedule, the project superintendent maintained a strict pace for steel erection, fabrication, and design. This coordination, coupled with tight collaboration between the general contractor and architect, resulted in the building being completed under budget and ahead of schedule in just over a year.

Outside of iconic structures, location-based scheduling found early traction in manufacturing. Goodyear in the 1940s and German airplane manufacturers in the 1930s employed similar pacing concepts. The idea spread to Japan, eventually becoming a cornerstone of the Toyota Production System, where it’s known as takt time – a method for maintaining consistent, stable production.

Why It Fell Out of Favor

Despite its proven effectiveness, location-based scheduling lost ground in the US after the introduction of CPM. Critics argued that Line of Balance schedules lacked the analytical rigor of CPM, dismissing them as merely visual communication tools. While research in the 1980s debunked this notion, the damage was done: CPM had already become the dominant scheduling method.

The Return of Paced Work

Over the past two decades, location-based scheduling has re-emerged, driven by a need for more practical, visual methods. The US Government utilized a paced system called “Short Interval Production Scheduling” during the Pentagon renovation in 2002. Further research in the UK led to the development of “week beat scheduling.” Olli Seppänen’s dissertation on the Location-based Management System also contributed to its revival.

Today, case studies are exploring the use of takt time for less repetitive construction projects. The key to effectively communicating a takt time plan remains the same: a location-based schedule, like a Line of Balance schedule, is essential. Whether represented in one, two, or more dimensions, space is a critical resource that must be integrated into any construction schedule.

The resurgence of location-based scheduling isn’t simply a revival of an old method; it’s a recognition that prioritizing space, pacing work, and maintaining visual clarity are essential for successful construction projects. The lessons learned from the Empire State Building and the Toyota Production System are as relevant today as they were decades ago